Update: With changes introduced in January 2013 you only need 1GB – live demo!

In one of my last blog posts I wrote about memory efficient ways of coding Java. My conclusion was not a bright one for Java: “This time the simplicity of C++ easily beats Java, because in Java you need to operate on bits and bytes”. But I am still convinced that in nearly every other area Java is a good choice. Just some guys need to implement the dirty parts of memory efficient data structures and provide a nice API for the rest of the world. That’s what I had in mind with

GraphHopper

GraphHopper does not attack memory efficient data structures like Trove4j etc. Instead it’ll focus on spatial indices, routing algorithms and other “geo-graph” experiments. A road network can already be stored and you can execute Dijkstra, bidirectional Dijkstra, A* etc on it.

Months ago I took the opportunity and tried to import the full road network of Germany via OSM. It failed. I couldn’t make it working in the first days due to massive RAM usage of HashMaps for around 100 mio data points (only 33 mio are associated to roads though). Even using only trove4j brought no success. When using Neo4J the import worked, but it was very slow and when executing algorithms the memory consumption was too high when too many nodes where requested (long paths).

Then after days I created a memory mapped graph implementation in GraphHopper and it worked too. But the implementation is a bit tricky to understand, not thread safe (even not for two reading threads yet), slower compared to a pure in-memory solution. But even more important: the speed was not very predictable and very ugly to debug if off-heap memory got rare.

I’ve now created a ‘safe’ in-memory graph, which saves the data after import and reads once before it starts. At the moment this is read-thread-safe only, as full thread safety would be too slow and is not necessary (yet).

Now performance wise on this big network, well … I won’t talk about the speed of a normal Dijkstra, give me some more time to improve the speed up technics. For a smaller network you can see below that even for this simplistic approach (no edge-contraction or edge-reduction at all) the query time is under 150ms and will be under 100ms for bidirectional A* (w/o approximation!), I guess.

In order to perform realistic route queries on a road network we would like to satisfy two use cases:

- Searching addresses (cities, streets etc)

- Clicking directly on the map to create a route query

The first one is simple to solve and it is very unlikely to avoid tons of additional RAM. But we can solve it very easy with ElasticSearch or Lucene: just associate the cities, streets etc to the node ids of the graph.

The second use case requires more thinking because we want it memory efficient. A normal quad-tree is not a good choice as it requires too many references. Even for a few million data points it requires several dozens of MB in addition to the graph! E.g. 80MB for only 4 mio nodes.

The solution is to use a raster over the area – which can be a simple array addressed by spatial keys. And per quadrant (aka tile) we store one array index of the graph as entry point. (In fact this is a quad-tree of depth one!) Then when a click on the map happened, we can calculate the spatial key from this point (A), then get the entry point from the array and traverse the graph to get the point in the graph which is the closest one to point A. Here is an implementation, where only one problem remains (which is solved in the new index).

Unfair Comparison

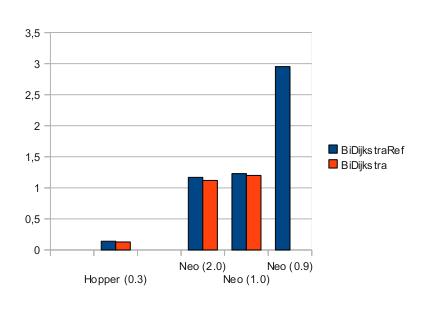

In the last days, just for the sake of fun, I took Neo4J and ran my bidirectional Dijkstra with a small data set – unterfranken (1 mio nodes). GraphHopper is around 8 times faster and uses 5 times less RAM:

The lower the better – it is the mean time in seconds per run on this road network where two of the algorithms (BiDijkstraRef, BiDijkstra) are used. The number in brackets is the actually used memory in GB for the JVM. The lowest possible memory for GraphHopper was around 160MB, but only for the more memory friendly version (BiDikstra).

For all Neo4J-Bashers: this is not a fair comparison as GraphHopper is highly specialized and will only be usable for 2D networks (roads, public transport) and it is also does not have transaction support etc. as pointed out by Michael:

But we can learn that sometimes it is really worth the effort to create a specialized solution. The right tools for the right job.

Conclusion

Although it is not easy to create memory efficient solutions in Java, with GraphHopper it is possible to import (2.5GB) and use (1.5GB) a road network of the size of Germany on a normal sized machine. This makes it possible to process even large road networks on one machine and e.g. lets you run algorithms on even a single, small Amazon instance. If you reduce memory usage of your (routing) application you are also very likely to avoid garbage collection tuning.

There is still a lot room to optimize memory usage and especially speed, because there is a lot of research about road networks! You’re invited to fork & contribute!